Content

- 1 What Is Thermal Spray and How Does the Process Work?

- 2 Major Thermal Spray Processes and Their Operating Principles

- 3 Supersonic Flame Spraying: HVOF and HVAF Processes in Detail

- 4 Tungsten Carbide Coating: Properties, Grades, and Industrial Use

- 5 Ceramic Thermal Spray Coatings: Materials, Processes, and Applications

- 6 Surface Preparation: The Foundation of Coating Quality

- 7 Post-Spray Treatments That Improve Coating Performance

- 8 Industry Applications: Where Thermal Spray Coatings Deliver the Greatest Value

- 9 Quality Control and Testing Methods for Thermal Spray Coatings

- 10 Choosing the Right Thermal Spray Solution: A Practical Decision Framework

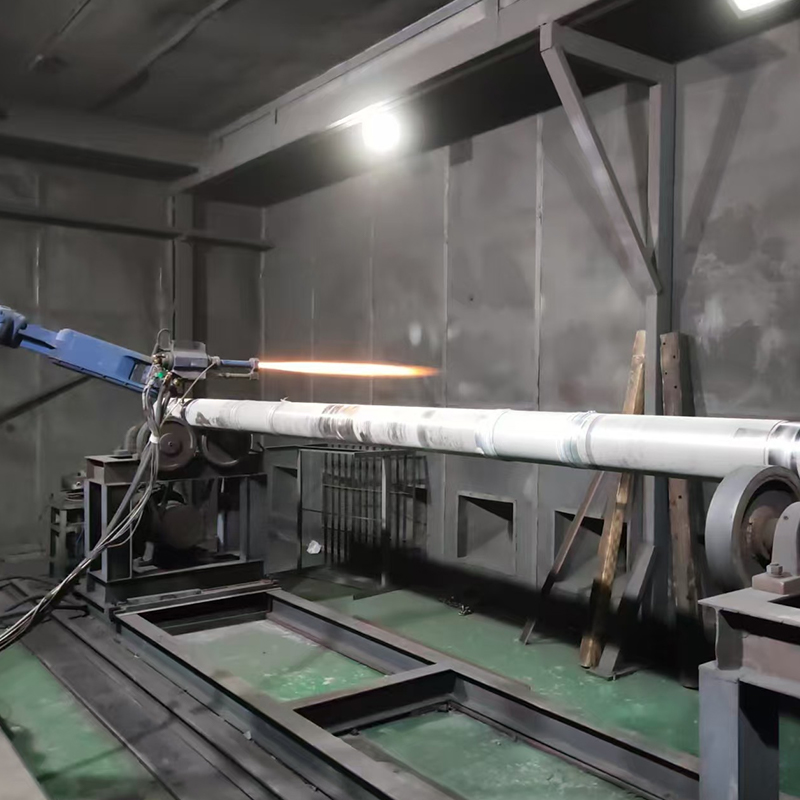

What Is Thermal Spray and How Does the Process Work?

Thermal spray is a group of industrial coating processes in which feedstock materials — supplied as powder, wire, or rod — are heated to a molten or semi-molten state and propelled at high velocity onto a prepared substrate surface. Upon impact, the particles flatten into thin, pancake-shaped "splats," interlock mechanically with the surface and with each other, and rapidly solidify to form a dense, adherent coating. The substrate itself remains relatively cool throughout the process, typically below 150°C for most methods, which means heat-sensitive components can be coated without distortion or metallurgical changes to the base material.

The fundamental physics driving thermal spray are straightforward: coating quality is governed by the combination of particle temperature and velocity at the moment of impact. Higher temperatures improve particle melting and inter-splat bonding, while higher velocities increase kinetic energy, reduce porosity, improve coating density, and enhance adhesion strength. Different thermal spray processes achieve vastly different combinations of these two parameters, which is why process selection is critical to matching coating properties to application requirements. Thermal spray can deposit metals, alloys, ceramics, cermets (ceramic-metal composites), and polymers onto virtually any substrate material — steel, aluminum, titanium, ceramics, glass, and even some plastics — making it one of the most versatile surface engineering technologies in industrial manufacturing.

Major Thermal Spray Processes and Their Operating Principles

The thermal spray family encompasses several distinct process variants, each differing in the heat source used, the achievable particle temperatures and velocities, and the resulting coating microstructure and properties. Understanding these differences is essential for engineers selecting a process for a specific application.

Flame Spray (Combustion Powder and Wire)

Conventional flame spray is the oldest and simplest thermal spray process, using the combustion of an oxygen-fuel gas mixture — typically oxygen and acetylene or propane — to melt the feedstock. Particle velocities are relatively low, in the range of 40–100 m/s, and particle temperatures reach approximately 3,000°C. The resulting coatings have relatively high porosity (5–15%), moderate adhesion strength (10–30 MPa), and are best suited for applications requiring corrosion protection, dimensional restoration, or simple wear protection at moderate cost. Flame spray is widely used for zinc and aluminum anti-corrosion coatings on structural steelwork and bridges.

Electric Arc Spray

Electric arc spray uses two consumable wire electrodes that are fed together and connected to opposite poles of a DC power supply. Where the wires meet, an electric arc melts the wire tips continuously, and a high-velocity compressed air or nitrogen jet atomizes the molten material and projects it onto the substrate. Arc spray is limited to electrically conductive feedstock materials — primarily metals and alloys — but delivers high deposition rates (up to 50 kg/hour) at relatively low operating costs. It is extensively used for large-area corrosion protection of offshore structures, ship hulls, and industrial storage tanks using zinc, aluminum, and Zn-Al alloy wires.

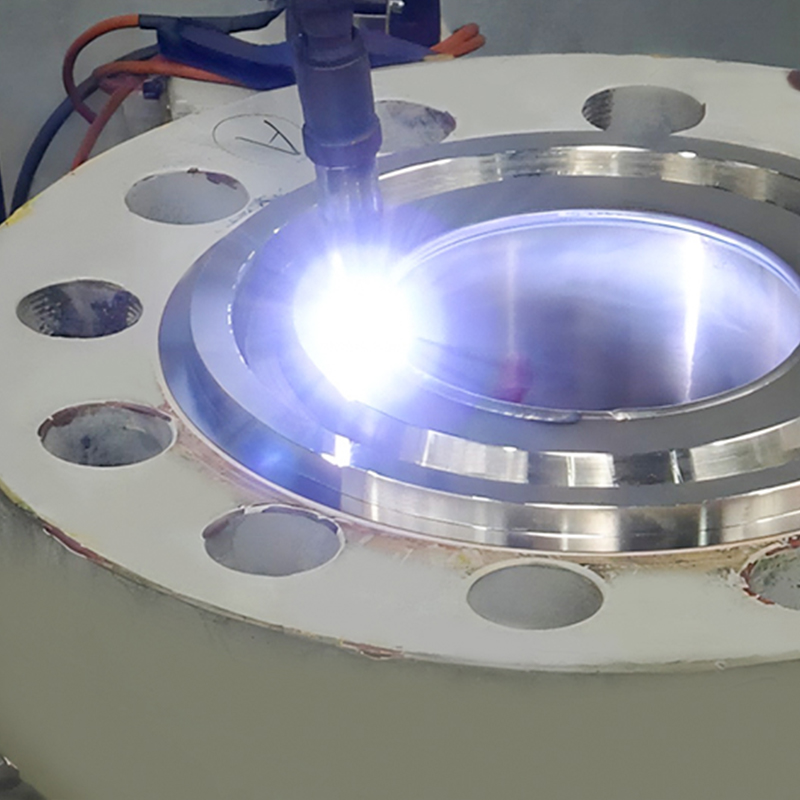

Plasma Spray (APS and VPS)

Atmospheric plasma spray (APS) generates a plasma jet by passing a gas — typically argon, nitrogen, hydrogen, or helium — through a high-frequency electric arc between a cathode and anode in a plasma torch. The plasma jet reaches temperatures of 6,000–20,000°C, far exceeding the melting point of virtually any material, including refractory ceramics and ultra-high-temperature compounds. Powder feedstock is injected radially or axially into this jet, melted, and accelerated to velocities of 200–600 m/s. APS is the dominant process for depositing ceramic coatings, including thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) of yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) on turbine blades and vanes, as well as alumina, chromia, and titania coatings for wear and corrosion applications. Vacuum plasma spray (VPS), operated in a controlled low-pressure chamber, eliminates oxidation during deposition and produces denser, higher-purity coatings for critical aerospace and medical applications.

Cold Spray

Cold spray is fundamentally different from other thermal spray processes: instead of melting the feedstock, it accelerates solid-state particles through a converging-diverging de Laval nozzle to supersonic velocities of 500–1,200 m/s using a high-pressure carrier gas (nitrogen or helium) heated to 200–1,000°C. Bonding occurs entirely through kinetic energy and plastic deformation upon impact, with no melting involved. This eliminates oxidation, phase transformations, and residual tensile stresses, producing fully dense, oxygen-free coatings with compressive residual stresses. Cold spray is increasingly used for copper electrical coatings, corrosion-resistant aluminum repair on aerospace structures, and additive manufacturing-like restoration of worn or damaged metal components.

Supersonic Flame Spraying: HVOF and HVAF Processes in Detail

Supersonic flame spraying encompasses two closely related high-velocity combustion processes — High Velocity Oxygen Fuel (HVOF) and High Velocity Air Fuel (HVAF) — that represent the most widely used thermal spray methods for depositing dense, hard, wear-resistant coatings in demanding industrial applications. Both processes achieve the combination of high particle velocity and controlled particle temperature that produces coating microstructures with very low porosity, high hardness, and excellent bond strength.

HVOF Process Mechanics and Equipment

In HVOF, a fuel gas — commonly hydrogen, propane, propylene, natural gas, or a liquid fuel such as kerosene — is burned with oxygen under high pressure (typically 5–10 bar) in a specially designed combustion chamber. The hot combustion gases expand through a converging-diverging nozzle to produce a supersonic gas jet at temperatures of approximately 2,700–3,100°C and velocities exceeding 1,500–2,000 m/s. Powder feedstock is injected axially into the gas stream at the nozzle throat, where it is carried along, heated, and accelerated. Particle impact velocities typically range from 600 to 900 m/s, producing coatings with porosity below 1%, hardness values exceeding 1,200 HV for WC-Co systems, and tensile adhesion strengths above 70 MPa. HVOF guns such as the Sulzer Metco DJ2700, Praxair Tafa JP-5000, and GTV HVOF system are industry standards used in aerospace, oil and gas, and tooling applications worldwide.

HVAF: The Lower-Temperature Alternative

HVAF replaces oxygen with compressed air as the oxidizer, which reduces the combustion temperature to approximately 1,900–2,000°C while maintaining or even increasing gas velocities compared to HVOF. The lower flame temperature is particularly beneficial for carbide-based feedstocks: in HVOF, the excessive heat can cause decarburization of tungsten carbide (WC → W₂C → W) and oxidation of the cobalt or chromium binder, degrading coating hardness and wear resistance. HVAF's lower temperature greatly reduces these deleterious reactions while the higher particle velocity still produces extremely dense, hard coatings. HVAF systems such as those from Uniquecoat Technologies and Kermetico have demonstrated WC-Co coating hardness values exceeding 1,400 HV with porosity below 0.5%, outperforming many HVOF benchmarks. Additionally, compressed air is far less expensive than industrial-grade oxygen, reducing operating costs by 40–60% compared to HVOF.

Comparing HVOF, HVAF, APS, and Cold Spray for Key Parameters

| Parameter | HVOF | HVAF | APS | Cold Spray |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame/Gas Temperature (°C) | 2,700–3,100 | 1,900–2,000 | 6,000–20,000 | 200–1,000 |

| Particle Velocity (m/s) | 600–900 | 700–1,000 | 200–600 | 500–1,200 |

| Coating Porosity (%) | <1 | <0.5 | 2–10 | <0.5 |

| Bond Strength (MPa) | >70 | >80 | 20–60 | >100 |

| Oxidation of Coating | Low | Very Low | Moderate–High | None |

| Best Feedstock Types | Cermets, metals, alloys | Cermets, metals | Ceramics, metals | Metals, alloys |

| Relative Operating Cost | High | Medium | High | Very High (He) |

Tungsten Carbide Coating: Properties, Grades, and Industrial Use

Tungsten carbide (WC) coatings deposited by supersonic flame spraying represent the gold standard for wear protection in the most demanding industrial environments. Tungsten carbide is one of the hardest materials known — bulk sintered WC achieves hardness values of 2,400 HV — and when combined with a metallic binder phase and deposited by HVOF or HVAF, it produces coatings that outperform hard chrome plating, electroless nickel, and most other surface treatments in abrasive, erosive, and sliding wear applications.

WC-Co: The Foundational Grade

WC-Co powder feedstocks, typically formulated with 12–17 wt% cobalt binder, are the most widely used tungsten carbide thermal spray composition. The cobalt matrix provides toughness and ductility to the inherently brittle WC phase, producing a cermet with an excellent balance of hardness (1,000–1,300 HV for HVOF coatings), fracture toughness, and wear resistance. WC-Co coatings are applied at thicknesses of 0.1–0.5 mm and are routinely used on pump plungers, hydraulic rods, slurry pump impellers, extrusion dies, and industrial roll surfaces. The primary limitation of WC-Co is its susceptibility to corrosion in acidic or chloride-containing environments, where the cobalt binder dissolves preferentially, undermining the structural integrity of the WC framework.

WC-CoCr: Enhanced Corrosion and Wear Resistance

WC-CoCr powder grades, most commonly WC-10Co-4Cr (10 wt% cobalt, 4 wt% chromium), address the corrosion limitation of WC-Co by incorporating chromium into the binder phase. Chromium forms a passive Cr₂O₃ oxide layer that resists attack in mildly acidic environments (pH 4–10) and marine atmospheres. HVOF-sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr coatings achieve hardness values of 1,050–1,250 HV, porosity below 0.5%, and corrosion resistance markedly superior to WC-Co in seawater and dilute acid exposure. This grade has become the preferred replacement for hard chrome plating in aerospace landing gear components, following regulatory pressure to eliminate hexavalent chromium electroplating under REACH and equivalent environmental regulations. Aircraft manufacturers including Boeing, Airbus, and their tier-1 suppliers have qualified WC-10Co-4Cr HVOF coatings as direct hard chrome alternatives on actuator rods, hydraulic cylinders, and undercarriage components.

WC-Ni and WC-NiCr: For Highly Corrosive Environments

For applications involving strongly corrosive media — including concentrated acids, alkalis, or high-temperature oxidizing gases — WC grades using nickel or nickel-chromium binders are specified. WC-12Ni and WC-15Ni coatings offer excellent chemical resistance across a wider pH range than cobalt-based binders, as nickel is inherently more corrosion-resistant. WC-NiCr grades, analogous to Inconel-family alloys, extend service temperature capability and provide oxidation resistance at temperatures up to 500°C. These grades sacrifice some hardness compared to WC-Co (typically 900–1,100 HV) but are essential in chemical processing equipment, paper and pulp machinery, and marine diesel engine components exposed to aggressive corrosive wear.

Carbide Particle Size Effects on Coating Performance

The size of the WC carbide particles within the powder feedstock significantly affects both the spraying behavior and the final coating properties. Conventional WC powders contain carbide grains in the 1–5 μm range. Submicron and nanostructured WC powders (carbide grains <500 nm) have been developed to exploit the Hall-Petch hardening effect — smaller grain sizes yield harder coatings. However, nanostructured WC powders are far more susceptible to decarburization during HVOF spraying because the higher surface area-to-volume ratio accelerates carbon loss reactions. HVAF spraying, with its lower flame temperature, is significantly better suited to nanostructured WC feedstocks and can produce coatings with hardness exceeding 1,500 HV with minimal decarburization. Bimodal WC powders — blending micron and nano-scale carbides — offer a practical compromise between hardness, toughness, and process stability.

Ceramic Thermal Spray Coatings: Materials, Processes, and Applications

Ceramic thermal spray coatings serve fundamentally different functions from metallic and cermet coatings. Their primary roles include thermal insulation (thermal barrier coatings), electrical insulation, resistance to oxidation and hot corrosion at extreme temperatures, and protection against abrasive and erosive wear in high-temperature environments where metallic coatings would oxidize or soften. The high melting points of ceramic materials — alumina melts at 2,072°C, zirconia at 2,715°C — make atmospheric plasma spray (APS) the dominant deposition process, as only plasma torches generate sufficient heat to fully melt these refractory materials reliably.

Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia (YSZ) Thermal Barrier Coatings

YSZ is the most important ceramic thermal spray coating material in terms of economic value and engineering criticality. Zirconia (ZrO₂) undergoes a destructive tetragonal-to-monoclinic phase transformation on cooling, which causes volumetric expansion and cracking. Adding 6–8 wt% yttria (Y₂O₃) stabilizes the tetragonal phase metastably at room temperature, creating a material with very low thermal conductivity (~2.3 W/m·K), high thermal expansion coefficient (~11 × 10⁻⁶ /°C), and excellent resistance to thermal cycling. APS-deposited YSZ TBCs are applied at thicknesses of 100–600 μm on the hot-section components of gas turbines and aero-engines — combustor liners, transition ducts, turbine vanes, and blades — over a metallic bond coat (typically MCrAlY alloy). The TBC reduces the metal surface temperature by 100–300°C, allowing turbine inlet temperatures to exceed the melting point of the nickel superalloy substrate, dramatically increasing thermodynamic efficiency and engine power output.

Alumina and Alumina-Titania Coatings

Alumina (Al₂O₃) thermal spray coatings are the workhorses of ceramic wear and electrical insulation applications. APS-deposited alumina coatings achieve hardness values of 800–1,000 HV and provide excellent resistance to sliding and abrasive wear, dielectric strength exceeding 15 kV/mm for electrical insulation, and good chemical resistance to many acids and alkalis. They are widely applied on textile machinery guides, pump liners, printing rolls, and electronic component fixtures. Alumina-titania (Al₂O₃-TiO₂) blends, most commonly in 3%, 13%, and 40% TiO₂ compositions, modify the pure alumina microstructure by introducing a rutile TiO₂ phase that acts as a binder between alumina splats, improving cohesive strength and reducing microcracking. The 13% TiO₂ blend is the most popular formulation, offering a balanced combination of hardness (~850 HV), toughness, and coating density superior to pure alumina at equivalent spray parameters.

Chromia (Cr₂O₃) Coatings

Chromia coatings deposited by APS are among the hardest ceramic thermal spray coatings achievable, with values reaching 1,200–1,400 HV — approaching those of HVOF-sprayed WC cermets. Chromia's exceptional hardness, combined with its chemical resistance to many organic solvents, weak acids, and alkalis, makes it particularly valuable in the printing and packaging industry for doctor blade counter-rolls (anilox rolls), in textile fiber guide applications, and in pump components handling mildly corrosive abrasive slurries. The distinctive dark green to black color of chromia coatings is a practical identifier in service. Chromia does not perform well in strongly reducing atmospheres or in contact with oxidizable metals at high temperatures, where it can act as an oxidizing agent.

Titania (TiO₂) and Spinel Coatings

Pure titania APS coatings offer unique tribological properties: TiO₂ exhibits a self-lubricating behavior under certain sliding contact conditions due to the formation of shear-favorable rutile phases, making it attractive for applications requiring low friction alongside modest wear resistance. Spinel coatings — MgAl₂O₄ and ZnAl₂O₄ — are used as thermal barrier undercoats and electrical insulating layers in induction heating equipment and resistance heating applications where the combination of electrical insulation and thermal stability at temperatures up to 1,400°C is required. Mullite (3Al₂O₃·2SiO₂) coatings are applied on silicon carbide and silicon nitride ceramic components in gas turbines to provide environmental barrier coating (EBC) functionality, protecting the silicon-based substrate from water vapor attack at high temperatures.

Surface Preparation: The Foundation of Coating Quality

Regardless of the thermal spray process or coating material selected, the quality of surface preparation performed before spraying is the single most influential factor determining coating adhesion strength and long-term performance. Thermal spray coatings bond primarily through mechanical interlocking — the molten splats anchor into the surface roughness profile — rather than through metallurgical or chemical bonding. Inadequate surface preparation is responsible for the majority of premature coating failures in field applications.

- Grit blasting: The most universally employed preparation method, using angular alumina (Al₂O₃) or steel grit propelled at high velocity to simultaneously clean the surface of oxides, contaminants, and previous coatings, and to create a controlled surface roughness profile. Ra values of 4–10 μm are targeted for most thermal spray coatings. Blasting media selection matters: alumina grit is preferred for substrates where iron contamination from steel grit is unacceptable, such as titanium or nickel superalloy components. Grit size and blast pressure must be optimized to avoid embedding media fragments in the surface or inducing excessive subsurface cold work.

- Chemical cleaning and degreasing: All surfaces must be free of oils, release agents, machining coolants, and organic contaminants before blasting. Solvent degreasing (acetone, IPA, or vapor degreasing) or alkaline cleaning is performed before grit blasting. Critically, the blasted surface must be sprayed within a defined time window — typically 2–4 hours for steel substrates in normal humidity — to prevent re-oxidation, which dramatically reduces adhesion.

- Masking and dimensional control: Areas not to be coated must be protected with reusable silicone masks, metallic plugs, or high-temperature masking tape. For precision-engineered components such as landing gear actuators or pump plungers, substrate dimensions must be verified before spraying so that final ground-and-finished dimensions meet tolerances after coating and post-spray grinding operations.

- Bond coat application: For applications requiring enhanced adhesion or to mitigate thermal expansion mismatch between substrate and topcoat — particularly for ceramic TBC systems — a metallic bond coat is applied before the ceramic topcoat. MCrAlY alloys (where M = Ni, Co, or Ni+Co) are sprayed by HVOF, VPS, or low-pressure plasma spray (LPPS) to thicknesses of 75–150 μm, forming a thermally grown oxide (TGO) layer during service that anchors the ceramic topcoat.

Post-Spray Treatments That Improve Coating Performance

As-sprayed thermal spray coatings often benefit from post-deposition treatments that refine their microstructure, seal residual porosity, improve surface finish, or relieve internal stresses. The appropriate post-treatment depends on the coating material, the application environment, and the required final properties.

Grinding and Lapping for Dimensional and Surface Finish Requirements

Most thermal spray coatings are deposited slightly oversized and subsequently ground or lapped to final dimensions and surface finish. For WC-Co and WC-CoCr coatings on hydraulic rods and landing gear, cylindrical grinding using diamond wheels achieves surface roughness values of Ra 0.1–0.4 μm, and dimensional tolerances of ±0.01 mm or better. Grinding parameters must be carefully controlled to avoid microcracking of the brittle ceramic or cermet coating, particularly in dry grinding: water-based coolants are essential. For ceramic coatings such as alumina, diamond grinding is similarly required, as conventional abrasives are insufficiently hard to efficiently machine these materials.

Sealant Impregnation

Thermal spray coatings inherently contain a network of interconnected and isolated pores. In corrosive environments, these pores provide pathways for electrolytic solutions to penetrate through the coating and attack the substrate. Sealant impregnation — applying low-viscosity organic sealants such as epoxy resins, phenolics, or PTFE-based compounds by vacuum impregnation or surface application — fills the open porosity and seals the coating against corrosive ingress. Sealing is standard practice for thermally sprayed zinc and aluminum anti-corrosion coatings on structural steelwork and for APS ceramic coatings in wet environments. For applications above 200°C, inorganic sealants based on phosphate or silicate chemistry must be used instead of organic materials.

Heat Treatment and Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP)

Vacuum or controlled-atmosphere heat treatment of thermally sprayed metallic coatings can promote inter-splat diffusion bonding, relieve residual stresses, and — for self-fluxing alloys such as NiCrBSi — trigger a liquid-phase sintering reaction that densifies the coating to near-zero porosity and creates a true metallurgical bond with the substrate. This "fusing" process, performed at 1,000–1,100°C, produces coatings with adhesion strengths exceeding 300 MPa, approaching the cohesive strength of the coating material itself. Hot isostatic pressing (HIP), applied to coatings on complex aerospace components, uses simultaneous high temperature and high inert gas pressure to close all residual porosity, and is specified for critical turbine components where any defect could be life-limiting.

Industry Applications: Where Thermal Spray Coatings Deliver the Greatest Value

Thermal spray coatings are employed across a remarkably diverse range of industries. The following table maps key industries to their primary coating requirements and the most commonly specified thermal spray solutions:

| Industry | Component / Application | Coating Material | Process | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerospace | Turbine blades, vanes, combustors | YSZ TBC + MCrAlY bond coat | APS / VPS | Thermal insulation, oxidation resistance |

| Aerospace | Landing gear, actuator rods | WC-10Co-4Cr | HVOF | Hard chrome replacement, wear + corrosion |

| Oil & Gas | Pump plungers, valve seats, drill stabilizers | WC-Co, WC-CoCr, Cr₃C₂-NiCr | HVOF / HVAF | Abrasive and erosive wear resistance |

| Power Generation | Boiler tubes, fan blades, turbine rotors | Cr₃C₂-NiCr, NiCrAlY, WC-Co | HVOF / APS | Erosion, high-temp oxidation resistance |

| Printing & Packaging | Anilox rolls, doctor blade counter-rolls | Cr₂O₃, Al₂O₃-TiO₂ | APS | Extreme hardness, ink release control |

| Medical Devices | Orthopedic implants (hip, knee stems) | Hydroxyapatite (HA), Ti | APS / VPS | Bone ingrowth, osseointegration |

| Marine & Infrastructure | Bridges, offshore structures, ship hulls | Zinc, Aluminum, Zn-15Al | Arc Spray / Flame Spray | Cathodic corrosion protection |

Quality Control and Testing Methods for Thermal Spray Coatings

Ensuring the quality of a thermal spray coating requires a systematic testing program that validates both the process parameters used during deposition and the final coating properties. Quality programs in aerospace and critical industrial applications are governed by specifications such as AMS 2447 (thermal spray coatings), AMS 2448, and customer-specific process approvals, which mandate documented testing at defined frequencies.

- Microhardness testing (HV0.3 or HV0.1): Vickers microhardness measured on metallographic cross-sections is the most common coating quality indicator. Minimum hardness values are specified for each coating grade — for example, WC-10Co-4Cr by HVOF must achieve a minimum of 1,050 HV0.3 per most aerospace specifications. At least 10 indentations are taken across the coating thickness and averaged, with rejection of any single value deviating more than ±15% from the mean.

- Porosity measurement by image analysis: Metallographic cross-sections are prepared by vacuum epoxy impregnation to preserve pores, polished to a 1 μm diamond finish, and examined by optical or scanning electron microscopy. Image analysis software measures the area fraction of pores, typically requiring porosity below 1% for HVOF cermet coatings and below 5% for APS ceramic coatings.

- Tensile adhesion testing (ASTM C633): Coating adhesion is measured by epoxy-bonding a dolly (25 mm diameter) to the coating surface, then loading it in tension until failure. The failure load is divided by the bonded area to give adhesion strength in MPa. The failure mode — adhesive (coating-substrate interface), cohesive (within coating), or epoxy failure — is documented as it provides diagnostic information about coating quality.

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) phase analysis: For WC-based coatings, XRD is used to detect and quantify decarburization products (W₂C, W metal) that form during excessive heating in HVOF. Specifications such as ASME requirements for WC-CoCr coatings on subsea valves place maximum limits on the W₂C content detectable by XRD, ensuring the spraying process was properly controlled.

- Thickness measurement by eddy current or magnetic induction: Coating thickness is verified using non-destructive electromagnetic methods on metallic substrates, or by profilometry measurements comparing pre- and post-spray surface profiles. Thickness conformance ensures that post-grinding operations will achieve specified final dimensions without exposing the substrate.

Choosing the Right Thermal Spray Solution: A Practical Decision Framework

Selecting the optimal thermal spray process and coating material for a specific application requires systematic evaluation of the service environment, substrate constraints, performance requirements, and economic considerations. The following decision framework guides engineers through the key questions:

- Define the primary failure mode: Is the component failing by abrasive wear, erosion, adhesive wear, fretting, corrosion, oxidation, or thermal fatigue? Each failure mode is best addressed by a specific coating class. Abrasion and erosion point to WC cermets by HVOF; thermal fatigue on hot-section parts points to YSZ TBC by APS; galvanic corrosion of steel structures points to arc-sprayed zinc or aluminum.

- Assess substrate temperature sensitivity: If the substrate is a heat-treated steel that must not exceed 150°C, HVOF or cold spray are appropriate; if it is a nickel superalloy turbine blade that can withstand high temperatures, VPS or low-pressure plasma spray is suitable. Polymer substrates require cold spray or specialized low-temperature flame spray processes.

- Evaluate geometry and access constraints: Large flat or cylindrical surfaces are easily coated with automated robotic spray systems. Complex internal bores, blind features, and undercuts present significant challenges for line-of-sight thermal spray processes and may require specialized gun configurations or alternative coating technologies.

- Consider volume and production economics: For high-volume automotive or consumer product components, arc spray or flame spray offers the lowest per-part cost. For low-volume, high-value aerospace or oil and gas components where coating performance directly determines asset life and safety, the higher operating cost of HVOF or HVAF is fully justified by the performance premium delivered.

- Verify regulatory and specification requirements: Aerospace applications governed by OEM or airworthiness authority specifications may mandate a specific process, coating material, and supplier qualification. Hard chrome replacement programs under REACH or US DoD directives specify HVOF WC-CoCr as the qualified alternative. Environmental permits may restrict the use of certain spray materials (e.g., cobalt-containing dusts require rigorous enclosure and filtration).

ENG

ENG

English

English عربى

عربى Español

Español 中文简体

中文简体

TOP

TOP